U.S. National Missing Children’s Day. How the FBI tracks children who disappear

Over 460,000 children went missing last year in the U.S. and law enforcement officers know the crucial role their fast response has in these cases. As May 25 marks National Missing Children’s Day, the FBI offers a glimpse into how such an investigation develops and, hopefully, ends with the safe return of the child.

How the U.S. established the National Missing Children’s Day and why 2017 is important in the story

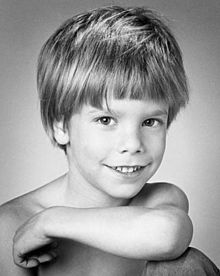

May 25 was established as National Missing Children’s Day in 1983, four years after the May 25, 1979 disappearance of Etan Patz, a 6-year-old New York City boy. The extensive media attention given to Etan’s disappearance has been credited with creating greater attention to missing children, resulting in changes such as less willingness to allow children to walk to school, photos of missing children being printed on milk cartons, and promotion of the concept of “stranger danger”, the idea that all adults not known to the child must be regarded as potential sources of danger.

On May 25, 1979, Etan left home by himself for the first time, planning to walk two blocks to board a school bus at West Broadway and Prince Street. He was wearing a blue captain’s hat, a blue shirt, blue jeans, and blue sneakers.

He never got on the bus. His teacher noticed his absence but did not report it to the principal. When Etan did not return home after school, his mother Julie called the police. An intense search began that evening, using nearly 100 police officers and a team of bloodhounds. The search continued for weeks. Neighbours and police canvassed the city and placed missing-child posters featuring Etan’s portrait, but this resulted in few leads.

As Etan’s father was a professional photographer and had a collection of photographs he had taken of his son, images of the 6-year-old were printed on countless missing-child posters and milk cartons and also made their way on screens in Times Square.

Despite efforts, Etan Patz was never found and he was declared legally dead in 2001.

Jose Antonio Ramos, a convicted child sexual abuser who had been a friend of Etan’s former babysitters, was identified in 1985 as the primary suspect. Ramos has denied that he killed Etan and the case was reopened in 2010. On May 24, 2012, New York Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly announced that a man was in custody who had implicated himself in Etan’s disappearance. A law enforcement official identified the man as 51-year-old Pedro Hernandez of Maple Shade, New Jersey, and said that he had confessed to strangling the child.

At the time of Etan’s disappearance, Hernandez was an 18-year-old convenience store worker in a neighbourhood bodega. He later said that he threw Etan’s remains into the garbage and was charged with second-degree murder. A New York grand jury indicted Hernandez on November 14, 2012, on charges of second-degree murder and first-degree kidnapping.

On December 12, 2012, Hernandez pleaded not guilty to two counts of murder and one count of kidnapping in a New York court. The case resulted in a mistrial in May 2015 due to a hung jury, which was deadlocked 11 against 1 for conviction. A retrial began on October 19, 2016, in a New York City court.

On February 14, 2017, Hernandez was found guilty of kidnapping and felony murder. On April 18, 2017, Hernandez was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 25 years.

A glimpse into an FBI investigation

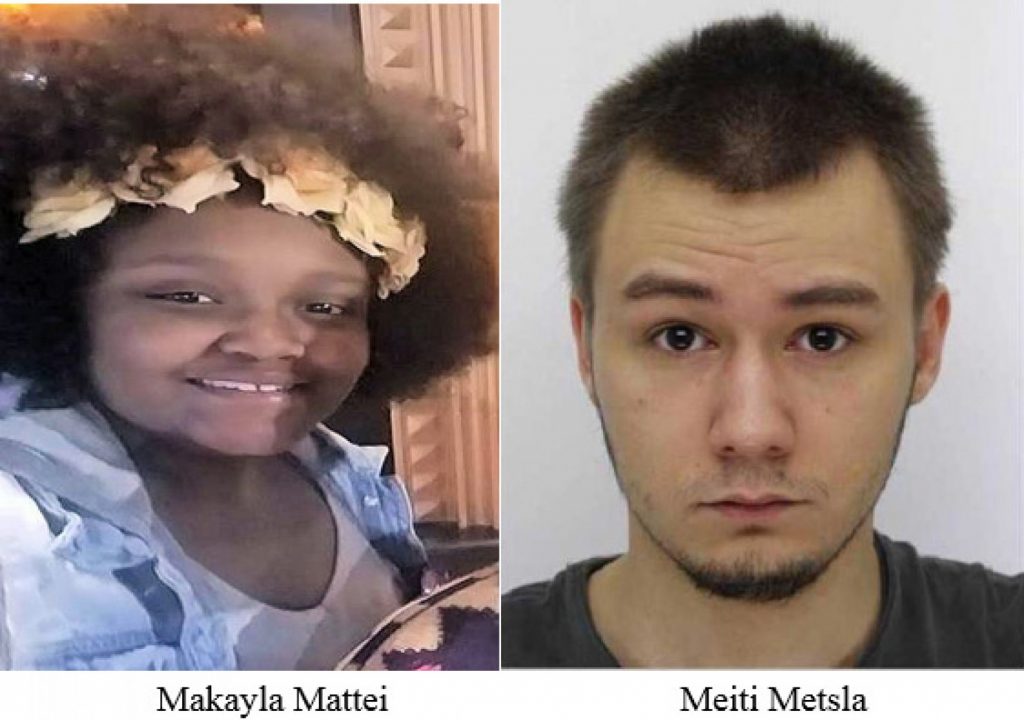

Makayla Mattei, a 15-year-old teenager from Virginia, was reported missing in February, but located safe and unharmed, just a few days later, with police arresting Meiti Metsla, a 21-year-old, for soliciting a child online, a felony. The way law enforcement responded and the FBI’s role when kids go missing offers a glimpse into such situations.

According to the U.S. agency, police were called when the girl was believed missing, setting in motion an intense process that relies on the resources, expertise, and partnerships of local, state, and federal agencies, including the FBI. Also alerted was the non-profit National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), which last year assisted with more than 20,500 cases of missing children — 90 percent of them endangered runaways.

Having determined the girl might be endangered — susceptible to human trafficking, child prostitution, or possibly the victim of abduction — local police referred the case to special agents in the FBI’s Washington Field Office (WFO). It was a smooth transition because the agencies work cases together on the region’s Child Exploitation and Human Trafficking Task Force, the FBI notes.

“We have a robust task force that includes most of the local agencies,” Ray Duncan, assistant special agent in charge of the WFO Criminal Division, said.

The agency says that once reported, the missing girl’s description was entered into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC), an index of criminal justice information available to every law enforcement agency in the country.

Special Agent Rob Bornstein, who supervises WFO’s Crimes Against Children squad, explains what happens next:

“Then we will try to step in as soon as possible because we believe those kids are clearly endangered. Timing is critical. The earlier we get involved the better.”

In this case, agents and analysts traced Makayla Mattei’s actions from the moment she arrived home from school, dropped off her backpack, and left the house again. Investigators coordinated with local and regional public transit agencies to collect video footage of the girl’s movements across the region, and then out of the state. They were able to determine that the girl had been sent a bus ticket, which revealed her destination — more than 1,000 miles away from home. The ticket ultimately led to the identity and location of a subject. Using other sophisticated techniques, the FBI was able to locate the subject that led to the missing child.

WFO investigators, including one of the Bureau’s specialized Child Abduction Rapid Deployment Teams, reached out to FBI agents in the field, as well as local authorities, to rescue the girl and make the arrest.

“We leverage our 56 field offices across the country—and our 64 legal attachés around the world—to work as a force multiplier. The amount of resources we bring to bear is intrinsic to solving these cases quickly. If we develop information that is outside our area of responsibility, we can contact our agents there to assist. That’s why this worked so well,” Timothy Slater, special agent in charge of the Criminal Division at WFO, explained.

Offenders moved from the streets to the World Wide Web

Reports of brazen abductions have gone down significantly over the years, largely replaced by online predators, according to Robert Lowery, Virginia-based agency’s Missing Children Division’s vice president.

“Offenders are still there and the threat still exists. Now they’re online enticing children,” Lowery said.

Special Agent Rob Bornstein adds that advances in technology, including encryption, are making it harder to find the bad guys. Bornstein also underlined the importance for parents to know who their children are communicating with, what they are posting, and what they are looking at on the Internet.

“We want parents to not be judgmental with their children if they bring something to their attention. Sometimes there’s a propensity for parents to be judgmental and blame the child for inappropriate conversation when, in fact, these offenders have set the stage for that conversation,” Lowery said.

The NCMEC says it encourages responsible use of social media—rather than fully restricting it, which may have a counter-effect—and honest communication between parents and their kids.

Numbers of children gone missing

The number of reports of missing kids last year rose by about 5,000, according to NCIC figures. Investigators said the confluence of kids using cell phones and their easy access to social media has made them more susceptible to predators. Still, the number of children reported missing has declined significantly since NCMEC was established in 1984 following the 1981 abduction of Adam Walsh, founder John Walsh’s 6-year-old son.

Many kids, however, remain missing. According to NCMEC, which assists law enforcement and families with missing child cases, about 18,500 of the missing children in 2016 were runaways, who may not want to be found. Posters featuring images and descriptions of missing kids can be found on the FBI website and at missingkids.org, NCMEC’s website. If you think you have seen a missing child, contact NCMEC at 1-800-843-5678 or contact your local FBI field office.

According to the FBI, in 2016 there were 465,676 National Crime Information Center (NCIC) entries for missing children. Similarly, in 2015, the total number of missing children entries into NCIC was 460,699.

This number represents reports of missing children. That means if a child runs away multiple times in a year, each instance would be entered into NCIC separately and counted in the yearly total. Likewise, if an entry is withdrawn and amended or updated, that would also be reflected in the total.

During the last 32 years, NCMEC’s national toll-free hotline, 1-800-THE-LOST® (1-800-843-5678), has received more than 4.3 million calls. NCMEC has circulated billions of photos of missing children, assisted law enforcement in the recovery of more than 237,000 missing children and facilitated training for more than 331,000 law enforcement, criminal/juvenile justice and healthcare professionals. NCMEC’s Team HOPE volunteers have provided resources and emotional support to more than 59,000 families of missing and exploited children.

The International Missing Children’s Day was also launched in 1998 as a joint venture of the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC) and the US’s National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), and the Global Missing Children’s Network (GMCN). The GMCN is a network of countries that connect, share best practices, and disseminate information and images of missing children to improve the effectiveness of missing children investigations. It has 23 member countries: Albania, Argentina, Australia, Belarus, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the US.