Researchers find link between heart disease and mental health

People with depression or anxiety have an increased risk of heart disease and researchers have just identified the reason behind this connection. They found the way two key areas of the brain govern both a person’s emotions and heart activity.

Dr Hannah Clarke and colleagues from the University of Cambridge and Cambridgeshire & Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust have discovered a link between two key areas of the brain and emotional responses. They also show that the human brain controls cardiovascular response – changes in heart patterns and blood pressure – to emotional situations.

According to a press release, researchers used marmosets with small metal tubes implanted into specific brain regions in order to administer drugs that reduce activity temporarily in that brain region. This enabled the researchers to show which regions caused particular responses. The marmosets rapidly adapt to these implants and remain housed with their partners throughout the study.

As the structural organisation of the prefrontal cortex of non-human primates including the marmoset is very similar to that of humans, the researchers were able to directly address this issue.

In the first task, the marmosets were presented with three auditory cues: one that was followed by a mildly aversive stimulus (a loud noise), one that was followed by a non-aversive stimulus (darkness), and one where the subsequent stimulus had a 50/50 chance of being either a loud noise or darkness. The task lasted just 30 minutes and they were exposed to this task a maximum of five days a week over a few months.

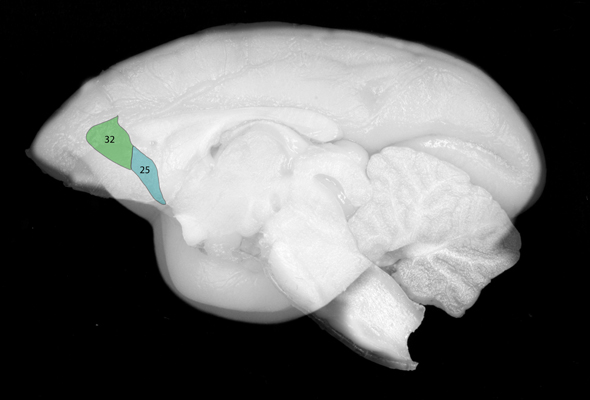

As the marmoset began to understand the cues, the researchers observed that the monkey’s heart rate and blood pressure increased in anticipation of the loud noise, and the monkey began to look around more (known as ‘vigilant scanning’). However, the team found that turning off one region (known as Area 25 – the subgenual cingulate cortex) of the prefrontal cortex in the marmosets made them less fearful: their heart rate and blood pressure did not change and they became less vigilant.

In a second task, adapted from a common rodent test of emotion, the team studied the ability of marmosets to regulate their emotional responses. In a single session of thirty minutes, an auditory cue was presented on seven occasions, and each time it was accompanied by a door opening and the marmoset being presented with a rubber snake for five seconds. As marmosets are afraid of snakes they developed similar cardiovascular and behavioural responses to the auditory cue associated with the snake as they did to the cue associated with loud noise. The next day, to break the link between the cue and snake, the researchers stopped showing the marmoset the snake when the cue was sounded.

In this task, inactivating Area 25 meant that the marmoset was quicker to adapt: once the link between the auditory cue and the snake was broken, the marmosets quickly became less fearful in response to the cue, with their cardiovascular and behavioural measurements returning to baseline faster than normal.

In both tasks, inactivating another region (Area 32 – the perigenual cingulate cortex) made normal fearful responses spread to non-threatening situations: the marmosets became less able to discriminate between fearful and non-fearful cues, showing heightened blood pressure and vigilant scanning to both. This is a characteristic of anxiety disorders.

“We now see clearly that these brain regions control aspects of heart function as well as emotions. This helps our understanding of emotional disorders, which involve a complicated interplay between brain and body,” Dr Clarke said.

The study was recently published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).