Visually impaired people can navigate using an MIT wearable system

Automatic navigation systems to aid the visually impaired have been in the works for decades, but computer scientists have found it difficult to come up with reliable and easy to use devices. As such, most visually impaired people still use the white cane to identify clear walking paths. Now, a team from MIT has developed a wearable system that provides information from a 3-D camera, via vibrating motors and a Braille interface.

As much help as they are for visually impaired people, white canes have their drawbacks. For example, when objects they come in contact with are other people and whether a chair or table is occupied.

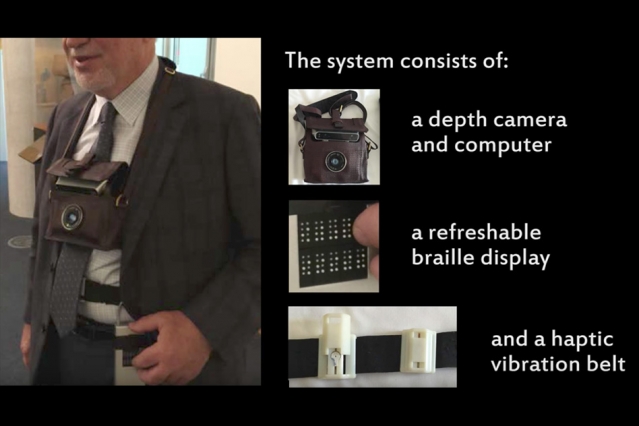

Now, researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have developed a new system that uses a 3-D camera, a belt with separately controllable vibrational motors distributed around it, and an electronically reconfigurable Braille interface to give visually impaired users more information about their environments.

“We did a couple of different tests with blind users. Having something that didn’t infringe on their other senses was important. So we didn’t want to have audio; we didn’t want to have something around the head, vibrations on the neck — all of those things, we tried them out, but none of them were accepted. We found that the one area of the body that is the least used for other senses is around your abdomen,” Robert Katzschmann, a graduate student in mechanical engineering at MIT and one of the paper’s two first authors, said.

According to the MIT News Office, the researchers’ system consists of a 3-D camera worn in a pouch hung around the neck; a processing unit that runs the team’s proprietary algorithms; the sensor belt, which has five vibrating motors evenly spaced around its forward half; and the reconfigurable Braille interface, which is worn on the user’s side. The key to the system is an algorithm for quickly identifying surfaces and their orientations from the 3-D-camera data.

In tests, the chair-finding system reduced subjects’ contacts with objects other than the chairs they sought by 80 percent, and the navigation system reduced the number of cane collisions with people loitering around a hallway by 86 percent.