How Beauty Standards Trotted Down the Catwalk of History: The Fashionistas of Yesteryear

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. An old adage of maiden freshness, it speaks of faded beauty ideals and the changing ideologies of physical attractiveness. For, in many cases, the beauty of the past would be the beast of today.

It’s enough to consider the atrocious foot binding of Chinese girls since the 13th century. The Rubenesque darlings strutting like plump cherubs on the Victoria Secret catwalk or les demoiselles d’Avignon breaking Instagram records with a selfie.

But how do we define beauty? According to what criteria does the passing of time judge the belles of the epoque, throwing ugliness into anonymity?

As it is, most beauty standards in history may actually be hardwired genetically. Contrary to feminist or anti-consumerist beliefs, sexual attraction has less to do with the patriarchy and Vogue’s promoted ideals of slender beauty and more with “evolved cues to virility and fertility, and hence, survival”, says Reza Ziai, a lecturer in psychology, in an interview for Areo Magazine.

Time exemplifies best how perception of physical attractiveness has been entirely subjective and a matter of social opinion depending on the age and the geographical whereabouts.

Beauty ideals have shifted in pace with groundbreaking art forms, the mysterious ways of fashion, and the whims of politicians- an absolute monarch could sign an on-the-spot edict denouncing the present ideal Size Six as ugly and the larger ladies as the norm for attractiveness.

Bulging tummies and receding hairlines were all the hip in feudal times of poverty and national hunger. Back then, snow white complexions and generous hips were the privilege of the patrician well-fed women, the city dwellers of leisure.

Transgressing borders of time and space, below we catch a few fleeting glimpses into the toilette of women and the artifice of beauty.

How Beauty Standards Changed Throughout History: It Sometimes Hurt, That’s For Sure

The Beautiful Boldness of Bald Women

Walk into any National Gallery and you’ll suddenly find yourself bewitched (beyond your control or reasonable understanding) by flocks of Renaissance portraits featuring dubious-looking ladies of means in the 16th century.

It’s the trademark of such Dutch or Italian paintings that stops the viewer in its tracks. Blonde to hair-bleached women with ivory complexions, their delicate extremities such as the chin, ears, cheeks and nipples painted in rosy hues, eyebrows plucked, and hairlines shaved so that the forehead could loom proud and mountainous in the eye of the beholder.

Evolution is known to monkey around excessively, but women did not grow bald out of nature’s mischief.

Italians called it arte biondeggiante and, contrary to what you might think, the receding hairline was done on purpose.

In the backyard of the court of Elizabeth I, wives of lords would douse their faces with “ceruse”, a type of make-up of white lead, powdered borax, and vinegar.

The effect was spectral to the point of a cadaverous shine, but more noteworthy were the side-effects: gout, anemia, scarring or kidney problems were some of the most prevalent diseases among high-class women of the court.

The Bronze Age of Painted Legs

The construction of a seductive public persona shifted chromatically in the 20st century. As pallor fell out of fashion- feminism empowered women to fight their battles not with swoons and oppressive fragility but to grab the bull by the horns- beauty standards took a shine to darker skin.

In the aftermath of the industrial revolution, tanning became a medical necessity. The lower working classes who lived in squalor and somber dwellings suffered from lack of sun and its related illnesses, from bone deformities, skin rickets to lupus vulgaris.

It wasn’t until Coco Chanel inadvertently glossed the covers of fashion magazines with a Mediterranean cruise sunburn that tanning burnt brighter within the public spectrum as the newest glamorous standard for beauty.

The more you managed the bronze look of a toffee-colored Aphrodite, the better your odds at being sculpted and subsequently devoured by the eyes of admirers.

However, not everyone was a socialite who could afford a day at the beach so women, in trying to emulate their earthly stars, would saturate their legs with Bovril.

This happened in the early 1940s but by the end of WWII, the thick meat extract was better off sent in bulk to the soldiers enduring in the trenches.

Stripped of sunbath opportunities, Bovril, nylon and silk stockings, women were suffering from “unashamed, pallid, bare legs that are conspicuous and unprovocative”, as Life Magazine reported.

To answer this national emergency, the cosmetic industry flooded the market with a variety of products that imitated the look of nylon.

Painted stockings going by the name of “Leg Film” and “Stocking Fizz” adorned the legs of women and the field of view of men. Ladies who could not afford the smart pantyhose, though, displayed even more ingenuity by using gravy to cook up their legs.

The Rappers Learned Grilling from the Corn-Loving Mayans

Head shaping and dental decoration were not invented by the anti-establishment rappers of the Bronx. Au contraire, grilling predates Outkast André 3000 by a few centuries.

Wealthy Mayans would insert gems, more specifically jades, into their teeth as a statement of fashion more than social status.

More gruesome was the procedure called trepanning by which the Mayans strapped the heads of their days-old children to cradleboards or other cephalic devices based on preHispanic Maya implements that in time would reconfigure the crania of infants to the desired mold.

Taking place at a rate close to 90%, both males and females underwent this method of compression. Neither gender nor social class could limit the Mayan’s right to strive for a beauty in the image and likeliness of their god- Yum Kaax, the Maize god.

According to its represented object of worship, Yum Kaax grew like an anthropomorphic image of corn.

And as the ear of the cereal narrows towards the top, so the Mayans would elongate their infants’ soft skulls like toothpaste squeezed from a dispenser.

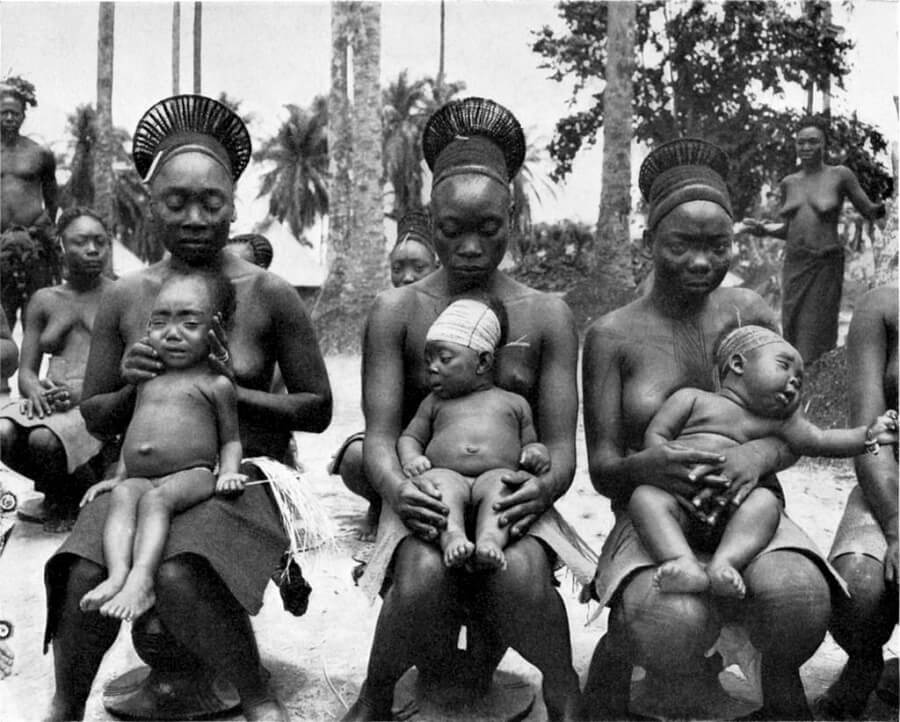

The Mangbetu, the nobility that inhabited the nooks of the Congo valley, freaked out the first European explorers with their elongated heads.

Known as Lipombo among the natives, the custom required that the skulls of babies were tightly wrapped with cloth until it shaped upwards in the following couple of years. The final product spoke of a higher status, majestic beauty and even a brighter mind.

This kind of beauty seemed to be a curse, Europeans felt, and so they banned the practice in the 1920s. However, it has long been discovered that, as long as the intracranial pressure does not go overboard, deformation will not affect the quality of the brain.

Not so for our next ideal of beauty in history.

The Giraffe Women of South-East Asia

One cosmetic procedure that has been heavily criticized by the medical world as uncontroversially damaging to health is still in practice in Northern Burma.

The Kayan women adorn their necks with brass coils, a unique accessory in the world of fashion which has earned them the title of “giraffe women”- a bit misleading as you’ll be hard to find any trace of the African ungulate mammals outside the sub-Saharan savannas.

Another optical illusion concerns the anatomical changes in the women’s bodies. The ritual starts at about age 5 and the ring snakes upwards to touch the chin, but in reality, the full 10-kilo weight of the coils is pressing down on the collarbone.

It is the rib cage that sinks further into the ground. But if the custom defies the universal laws of gravity, it adheres in change to the local standard for beauty.

The origins of this cosmetic surgery now lie in obscurity, as it is customary. Other theories speak of the brass coils as protection against tiger bites or an attempt on the part of the Padaung women to look more like the country’s legendary founder, the dragon.

The bizarre custom of the foot-long neck has been fading away like a ship in the agitated waters of a stormy sea when the civil wars boomed in Burma and sent the Padaung women into forced exile in Thailand.

The Thais soon saw the money-making opportunities in displaying “the giraffe women” as curious tourist attractions for the amused Western visitors.

The Rubenesque Wobbly Bits of a Chinese Tang Woman

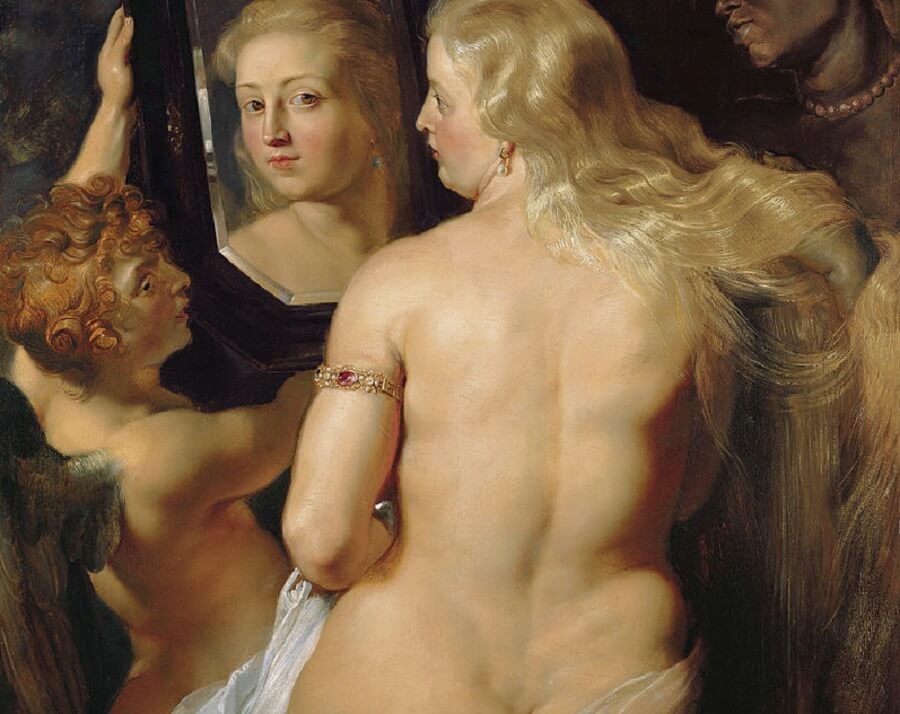

Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens was not alone in taking delight at womanly shapes that were as plump and generous as plush pillows.

The Chinese of the Tang dynasty also preferred their ladies of court to boast round, half-moon cheekbones, eiderdown bottoms, wide foreheads, and fleshy bodily curves.

In contrast, the eyes, mouth, and nose needed to be as veiled and submissive as genetically possible. Could it have anything to do with their roles as channels of perception and communication?

Once the Chinese despots succeeded one another by way of murder and palace intrigue, so did the court painters changed their attitudes and started portraying beauty in less voluptuous forms.

The Obsidian Smile of a Japanese Bride

“You can only hold a smile for so long, after that it’s just teeth.”, Chuck Palahniuk once penned.

Could the writer have been obsessing about the obsidian-hued smiles of the old Nippon women?

In typical Japanese exoticism, the Ohaguro practice of dyeing the teeth pitch black resisted as a beauty ideal and the privilege of emperors and high-ranking aristocrats for centuries.

To display a smile that resembled a terrifying black hole with the power to guzzle the viewer into the event horizon was reserved to married women, although men occasionally partook of the custom.

The beauty recipes involved iron fillings dissolved in vinegar and mixed with powdered tea, oyster shells, and gallnut.

The dental coating also prevented tooth decay but, more importantly, it excluded the obnoxious routine of brushing one’s teeth.

Raise an Eyebrow If It Looks Out of Fashion

In tracing how beauty standards have changed over time, take note from Cara Delevigne and let the eyebrows act as storytellers. From ancient Greece to feudal China, much plucking, tweezing, painting, and elongating the eyebrows was done.

Today, knitting one’s eyebrows translates to an attitude of confusion. In the Greece of the Olympian gods, eyebrows were the focal point of the face and thus, much fussed about. The touch up consisted of bridging the eyebrows together through a line of black incense.

A uni-brow delivered a bold look that spoke of intelligence and passion, two qualities that unwed girls were eager to display in order to gain the affections of an unbound Achiles.

As the hyper-religious Middle Ages sought to distance themselves ideologically from the damned excesses of the ancients, the overplucked style became all the rage.

A furry look symbolized loose sexuality, an attitude the Church could burn at the stake if it so willed. Driven by fear or the impulse to be fashionable, women would pluck their eyebrows with tearful dedication until their forehead beamed hairless and immaculate.

Angels would weep at the sight of their browless beauty.

In the Han dynasty of China, ladies would glorify their eyebrows by turning them into peacock-plumage. They would dash them green, black, blue, or any other color to come in stark contrast to their porcelain-white skin.

One particular style was deemed the “sorrow brow” and it involved curving arches that pointed upwards in an expression of fragile melancholy.

“Prince Albert” Piercing Victorian Moral-Codes

In the mystifying and hidden world of Victorian sexuality, formality and social etiquette took precedence over all considerations of style.

However, this prudish moral climate knew a few slips into the gutters of indecency. The quick rise and faster fall of nipple piercings has been well documented as a curiosity of Victorian England.

Inside the intimate circles of such hardcore fashionistas, the piercing were known as a “Prince Albert” since the vox populi had spread the word that the royal figure himself branded the look.

The wealthy lords leisuring it out in the shadows of the Buckingham Palace adopted the trend and spiced it up with a couple of gadgets of their own imagination. Women would connect their nipple ring-style adornments with a chain while men pierced their penises with a Victorian “Prince Albert”.

The carnal beauty of the world may be but skin-deep, but remove its makeup- the mass-media fabrications of the glamorous Size-Six or the self-interests of an all-powerful cosmetic industry- and you’ll uncover the beauty at dawn.

The puffiness of that puzzled look heavy with the old dreams of Mangbetu’s elongated skulls, teeth of an obsidian blaze, and a tanned Coco Chanel descending into the French harbor with the grace and the Breton stripes of a giraffe woman.