Does your name actually match your face?

Sometimes you look at someone and say “He’s such a Peter”. But do faces and names actually match? And if so, how is it even possible?

According to this new research, people believe some faces and names go together and they prefer it when they match. It turns out, people with round faces should have names that sound “round”, as the Independent reports. Names like Bob and Lou seem to fit them better, as it requires a rounding of the mouth. Similarly, people with more angular faces go better with “angular” names, like Peter.

Researchers from the University of Otago in New Zealand tested their theories by asking people to look at pairs of faces and names. Some names matched the faces, while others didn’t. People preffered it when they matched. Furthermore, the researchers found that people are more likely to vote for political candidates with names that match their faces. “Those with congruent names earned a greater proportion of votes than those with incongruent names,” lead study author David Barton said.

Data from Senatorial election in the US was analyzed. “The fact that candidates with extremely well-fitting names won their seats by a larger margin – 10 points – than is obtained in most American presidential races suggests the provocative idea that the relation between perceptual and bodily experience could be a potent source of bias in some circumstances,” Barton explained.

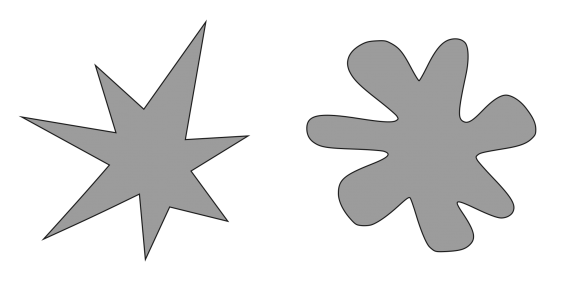

The study was based on the “bouba/kika effect”:

When shown the above two shapes and asked to match each one with the name “bouba” or “kika”, more than 95% people chose the rounded shape on the right and kika for the spiky shape on the left. The effect works in various languages.

“People’s names, like shape names, are not entirely arbitrary labels,” professor Jamin Halberstadt, who co-authored the study said. “Face shapes produce expectations about the names that should denote them, and violations of those expectations carry affective implications, which in turn feed into more complex social judgments, including voting decisions.”