The labour market is dominated by insecurity. Middle jobs are most affected

The number of people in work in the developed world has surpassed the levels before the 2008 economic crisis, but the newly created jobs are increasingly more polarising and insecure, an influential economic group has found.

The annual jobs report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), published revealed labour market conditions are continuing to improve in the 35 of the world’s wealthiest nations.

The OECD Employment Outlook 2017 found that the employed share of the population aged 15 to 74 years rose for the third consecutive year. It is expected to reach 61.5% by the end of 2018, above its peak of 60.9% in the fourth quarter of 2007.

However, the report highlighted what the OECD called a “paradoxical” moment for the developed world: employment is rising but so is workers’ anger about globalisation and inequality.

In addition, the labour market recovery remains highly uneven on the OECD states. The employment rate is likely to be only 1% above its pre-crisis level by the end of 2018. Large jobs deficits will persist in some countries, notably in Southern Europe. Even in countries where employment has recovered, wage growth is stagnant.

The report also projects that the labour market will continue to improve until at least the end of 2018, with nearly 47 million more people employed than at the end of 2007.

Labour market is dominated by insecurity

While a growing majority of the OECD countries finally succeeded to close the serious jobs gap that opened during the economic crisis and unemployment rates continued to fall, more and more people expressed an increasing dissatisfaction with the outlook of the jobs security and economic performance.

Since the economic crisis in 2009, both OECD and non-OECD economies have been on a lower growth trajectory than before the crisis. The slow pace of economic growth has also led to stagnation of income growth that people earning lower and middle incomes were already starting to experience due to inequality.

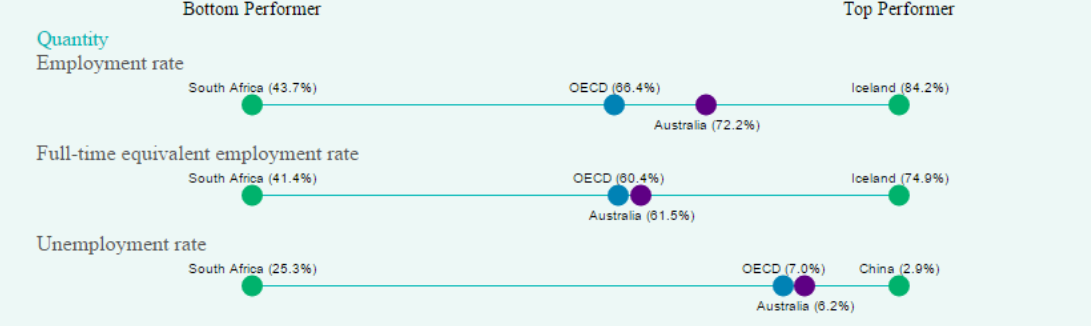

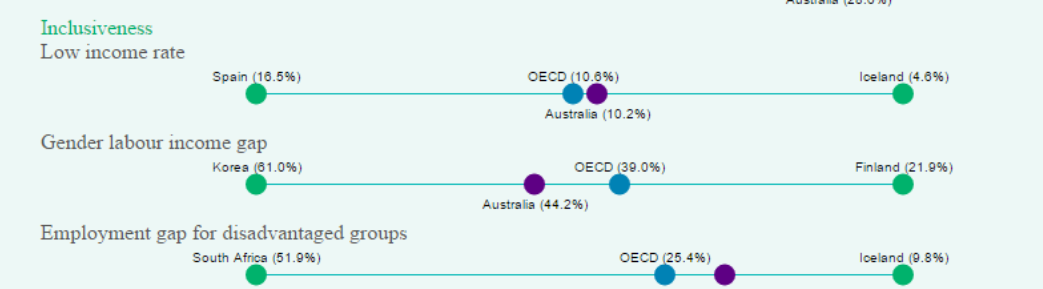

Iceland registers the best employment rate of 84,2%, while South Africa has the lowest one 43, 7% compared to the 66,4% OECD average.

In the OECD area, the average disposal income of the richest 10% of the population is now more than nine times that of the poorest 10%, up from seven times 25 years ago.

Unfortunately, the good news was tempered by the discovery that many of the newly created jobs offer stagnant pay and no career prospects.

“While the job gap is closing, many people do not feel the benefits as they are facing stagnant wages and no career prospect: we need an inclusive labour market that reconnects the benefits of our economic model with those who work in it,” said Angel Gurría, OECD secretary-general.

The labour market continues to be dominated by insecurity and inequality. For example, while OECD projected that Germany’s employment rate will be 9 percentage points above its pre-crisis level by end 2018, the OECD average will only be 1 percentage point above. Large jobs deficits will persist in some countries, including Greece, Spain, Ireland and Italy.

Fewer middle-skilled jobs and stagnant pay

The job market continues to improve in the OECD area, with the employment rate finally returning to pre-crisis levels. But people on low and middle incomes have seen their wages stagnate and the share of middle-skilled jobs has fallen, contributing to rising inequality and concerns that top earners are getting a disproportionate share of the gains from economic growth, according to a new OECD report.

Even in countries where employment has recovered, wage growth remains subdued and the occupational structure of labour markets is changing significantly, making it difficult for some workers to find rewarding employment opportunities.

Even though certain jobs have been displaced by imports, OECD stresses that new technologies, such as those associated with the new production revolution and digitalisation, play an even bigger role in the disruption of labour markets.

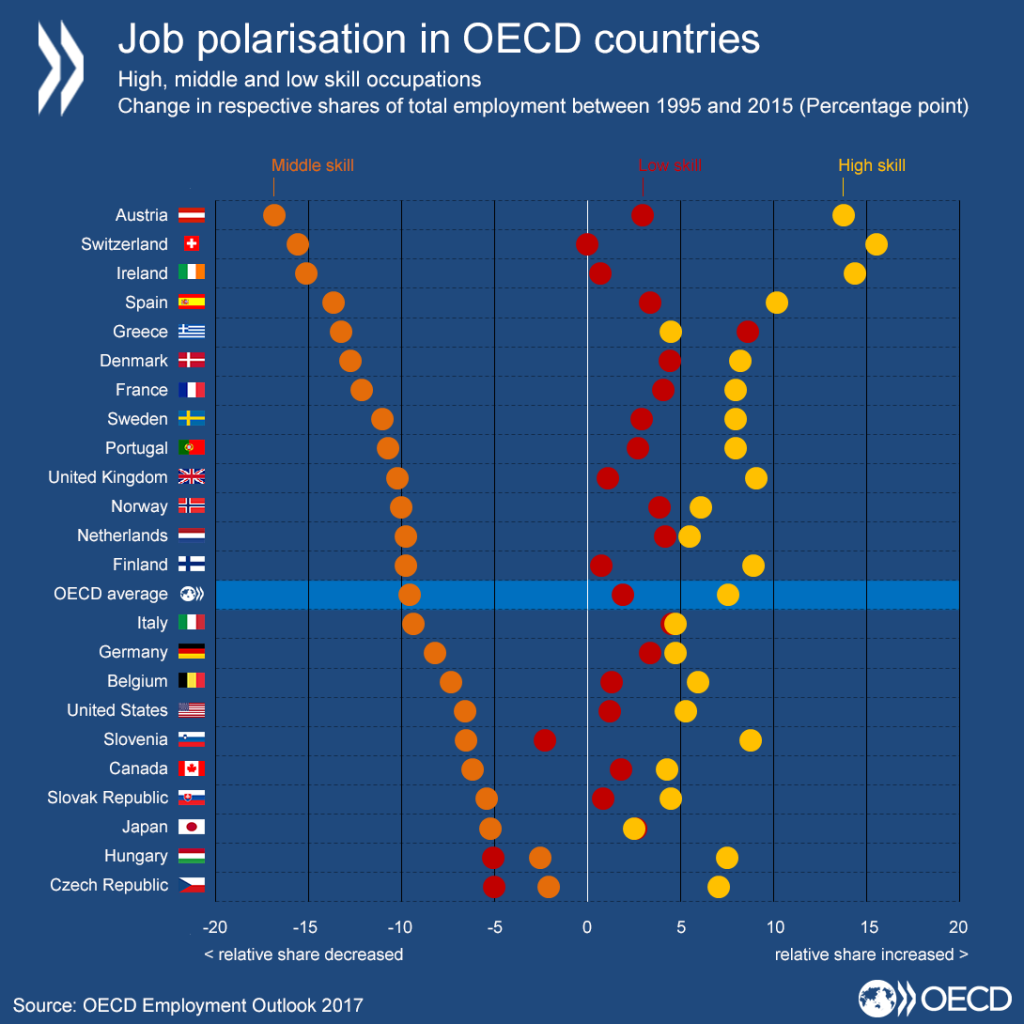

The organisation’s research showed that labour markets had been “hollowed out” across the developed world, with fewer roles in the middle of the jobs ladder and more at the top and bottom. The share of employment in “middle-skilled” jobs fell 9.5 percentage points between 1995 and 2015 in the OECD area, while the share of high and low-skilled jobs rose 7.6 and 1.9 percentage points respectively. In all OECD countries, high skilled workers have two to three times as many opportunities to participate in on-the-job training as their low-skilled counterparts.

Iceland is one of the safest labour markets, while Greece is at the opposite end. Regarding earnings quality, the Netherlands has the best rate of $ 29.2 per hour, while in India is the worst of $1.1 per for the gross hourly earning.

About a third of this polarisation was owing to the destruction of factory jobs and their replacement with lower-skilled service sector roles. The rest was because of polarisation within industries. The OECD attributed this more to the development of new technologies than to globalisation, though it said the two trends were difficult to disentangle.

Unemployment rate set to rise in the UK

Unemployment in the OECD area has fallen by 12 million people since peaking in the first quarter of 2010 and youth unemployment is down by 3.8 million. The OECD average unemployment rate is projected to further inch downwards from 6.1% at the end of the first quarter of 2017 – 38 million unemployed – to 5.7% in at the end of 2018 – 36 million unemployed.

The UK’s unemployment rate is expected to increase next year amid a slight deterioration of labour market conditions. At the end of last year, the UK unemployment rate was 4.8% compared with an OECD average of 6.2%, while the employment rate was 4% higher at 65.5%.

But in its latest employment outlook, the Paris-based organisation said: “The projections for 2017-18 anticipate that UK growth will ease as rising inflation weighs on real incomes and consumption, and business investment weakens amidst uncertainty about the United Kingdom’s future trading relations with its partners.

“A slight deterioration of labour market conditions is expected to bring its unemployment rate closer to the OECD average of 5.7% by the end of 2018.”

Good news: smaller gender pay gap and better integrated disadvantaged group

There was good news too: most countries narrowed their gender pay gaps and better integrated disadvantaged groups such as the disabled into the labour market. European countries faced with fiscal problems, such as Spain and Greece, experienced a fall in most of their labour market metrics, while Germany, Israel and Poland managed to improve most of theirs.

The gender labour income gap is obtained by calculating the difference between average annual labour income of men and women divided by the average income of men. Finland has the best result in this area, while in Korea, Mexic and Japan the gender labour income gap is the most accentuated.

The OECD has also reassessed its policy advice to member countries on how to improve their labour markets, becoming more supportive of trade unions, especially when collective bargaining is centralised. “Labour market adjustment to structural change is likely to proceed more smoothly and leave fewer workers behind if trade unions or other forms of worker representation allow workers’ interests to be taken more fully into account,” the report said.

The report warns that governments must help workers build the right skills, and give them the opportunities to upskill and reskill throughout their working lives. Countries should also better assess changing skill needs, adapt curricula and guide students towards choices that open up labour market opportunities. In all OECD countries, high skilled workers have two to three times as many opportunities to participate in on-the-job training as their low-skilled counterparts.