Brexit, an opportunity or a step towards disaster for UK’s agriculture sector

Brexit gives Britain the opportunity to negotiate for the first time in over 40 years new trade terms with the European Union. But this negotiation process is much more complicated than you would think as the UK is currently dependent on trade with the EU.

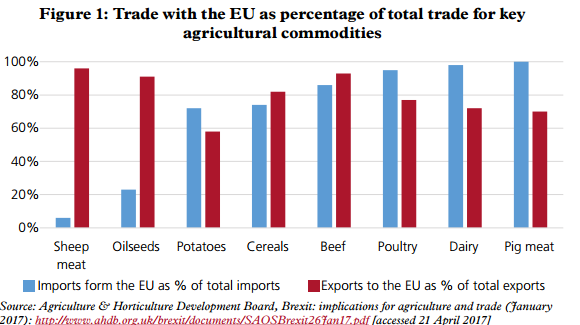

The agri-food sector in the UK, including agriculture, food manufacturing, food wholesaling, food retailing and food non-residential catering accounted for 7,2% of the national Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2014, the equivalent of £108 billion. Only the agriculture sector accounted for £9,9 billion. But around 80% of the agricultural exports are made in the European Union and facilitated by the Single Market.

More over, “the overwhelming majority of trade – over 70% of exports and vital imports – is with the EU member states and 94% of imports and 97% of exports are with countries with which the EU has negotiated Free Trade Agreements,” according to food manufacturers and processers.

The EU set a number of standards for food, farm animal health and welfare and plant production products, including the regulatory framework that governs genetically modified organisms. How Britain is going to substitute these regulations and how it will be able to maintain exports and food quality standards after Brexit remains to be seen. Here are a few challenges the UK is going to have to overcome.

What will happen when UK leaves the Single Market

Once the Brexit process will be completed, UK’s membership in the Single Market and customs unions will cease and the only option left will be getting a Free Trade Agreement with the EU, as Prime Minister Theresa May mentioned a number of times before triggering Article 50.

Without a Free Trade Agreement, thw UK will trade under the framework governed by the World Trade Organization (WTO), according to a report published by the House of Lords. But here we can already find one of the challenges that British lawmakers will have to take into account.

UK is a member of the WTO in its own right, even if the EU is the one representing Member States at the WTO, but must separate WTO schedules – commitments regarding the market access, domestic support and export competition – from those of the EU.

Optimist experts predict that this will give Britain the opportunity to become a leader in global free trade and expect lower prices for all consumers.

“Leaving the European Union and its Customs Union is a precondition for the UK to become a leader in global free trade, boosting our exports and lowering prices for all consumers. It is estimated that prices will be reduces overall by around 8%, with the price of food dropping by around 10%,” said the former Secretary of State for Scotland, Lord Forsyth of Drumlean.

“The UK is a very attractive market. It is a big, prosperous market and it is a net importer of food. Therefore, a lot of countries will be very interested to try to improve their access to this market,”Alan Matthews, Professor Emeritus of Agricultural Economics at Trinity College Dublin.

When it comes to imports, if things don’t go as planed, Britain must negotiate to retain, at least for a short period of time, the EU’s tariff schedules as its agricultural markets remain protected by high tariffs. If not successful, Britain will feel the impact higher tariffs will have on imports – like higher costs for consumers. Lower tariffs could also be detrimental as they could reduce the cost of food for consumers, but also undermine the domestic agricultural sector’s competitiveness.

“Should the UK fail to reach agreement with the EU … and fall back to trade under World Trade Organization terms, this would entail significant risk for sections of Scottish agriculture, such as cattle and sheep,” said Scott Walker, CEO at NFU Scotland.

“The effects of trading with the EU under the WTO rules on Welsh agriculture, fisheries and food will be very significant. Products from these areas will be hit by some of the most extreme tariffs under the WTO rules. It has been predicted trade opportunities in food related areas may fall by around 70–90%,” also explained Carwyn Jones, First Minister of Wales.

Also dependent on tariffs is a significant volume of animal feed imported from EU or non-EU countries vital to UK’s pig and poultry sectors, that rely on imported vegetable protein in quantities that can’t be replicated domestically to feed farm animals.

Customs procedures can also create delays that would have a negative impact on the agri-food sector as the food supply chains across the UK are highly integrated and products are often perishable.

New trading opportunities, hormone-treated beef and GMOs

Brexit will enable UK to search for new markets and sign trade agreements with a number of non-EU countries, such as China or US.

“We want to look for new markets, particularly for what we call fifthquarter products, which are products that British and European consumers do not eat, that go to China or wherever. We certainly see that if those could be opened it would give us a better return for those particular products that currently we have to pay to dispose of,” said Wesley Aston, Chief Executive of the Ulster Farmers’ Union.

Brexit will give Brits the opportunity to become “masters of their own import standards“, as the Chief Veterinary Officer suggested, as the country will have the liberty to relax some of the strict EU regulations.

This will also give British authorities the perfect opportunity to redesign the policy for food and farming, creating “a source to do food differently, to create new policies and systems to address the failing of the current food system”, according to Food Research Collaboration representatives.

But with this power also comes the challenge of keeping the food and feed standards high. In the absence of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the key EU regulator, UK must come up with its own framework to manage imported products that come from non-EU countries that have less rigid standards in the agri-food sector, such as the US.

“Past negotiations between the EU and US have raised wide-spread concern about agriculture – in particular facilitating the access of genetically modified foods, chlorine washed chickens and beef form cattle treated with growth promoting hormones. This is a logical objective for US negotiators in future UK-US deals,” explained George Dunn, Chief Executive of the Tenant Farmers Association.

Imports of beef produced with growth hormones have been banned in the EU since 1989 due to concerns regarding the risks hormone residues could have on human health.

Britain will also have to solve the issue of genetically modified organisms – food and feed. At this moment GMOs are strictly regulated in the Union, with only small amounts of GM maize being produced in a few member states, as only two GM crops have been approved for cultivation and only one, the insect-resistant Bt maize MON810, is actually cultivated in Europe. Several member states have issued bans on the cultivation of one or on both of these GM maize crops, but farmers outside the EU are allowed to grow a number of varieties.

Don’t forget that Europe is dependent on imports of GM products. Europeans need these products, for example, to feed farm animals. Member States import large quantities of GM soybean, one of the best sources of protein, and also rely almost entirely on imports when it comes to cotton. Some of the largest suppliers of GM products for the EU are Brazil, US and Argentina. More than half of the GM crops approved for import and processing and for food and feed in Europe are types of GM maize, but imports also include soybean, rapeseed, sugar beet and cotton.

UK will need to decide if it will allow cultivation of GMOs, but also if it will approve more GM crops for import. Making sure these products are safe for food and feed, a duty that currently falls on the EFSA who has scientific experts to asses GM crops and ensure that the products are at least as safe for human and animal consumption as the conventional counterpart, will also be a challenge for Britain.

Some experts hope UK could become an observer at EFSA such as Switzerland, others say they see no way for UK to participate directly at EFSA. In the end, UK bodies, such as the food inspection agencies, will probably need additional resources if they are to take on roles currently fulfilled by EU institutions.

Financial support for farmers and the workforce challenges

Many British farmers rely on EU financial support to keep their businesses viable. The CAP, a system of financial support measures and programmes under which farmers in the UK and the rest of the EU work and that covers areas such as farming, environmental measures and rural development, represents over 36% of the EU budget over the Multiannual Financial Framework for 2014-2020, according to the report published by the House of Lords.

The UK was expected to receive €25,1 billion in direct payments and €2.6 billion in rural development funds over this period of time.

After Brexit, UK will withdraw from CAP and the agriculture sector will have to compete with other sectors for public expenditure and will need to make a strong case in order to maintain financial support. This is why farmers will need a transitional period in order to adjust to a new financial support scheme.

In 2015 the agricultural workforce consisted of around 429,000 people. Britain will need to access foreign labour after Brexit, as this sector is highly dependent on not only seasonal, but also permanent, skilled and unskilled workers from the rest of the EU.

Loosing this labour pool could severely affect the food supply chain. This is another challenge lawmakers must take into account as foreigners could be discouraged to come work in the UK due to uncertainty. Rights of EU nationals that remain and work in the UK will need to be clarified.