MIT scientists control water using only light

Engineers at MIT developed a new system that can allow them to control the way water moves over a surface, using only light. The advancement could lead to new technologies, researchers say, pointing to microfluidic diagnostic devices or systems to be used for separating water from oil at drilling rigs.

MIT associate professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi, School of Engineering Professor of Teaching Innovation Gareth McKinley, former postdoc Gibum Kwon, graduate student Divya Panchanathan, former research scientist Seyed Mahmoudi, and Mohammed Gondal at the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals in Saudi Arabia, are behind the system which had as an initial goal to find ways of separating oil from water, for example, to treat the frothy mixture of briny water and crude oil produced from certain oil wells.

According to a press release, the team explored the use of “photoresponsive” surfaces. When exposed to light, the response of these surfaces to water is altered and by creating such surfaces – with a property known as wettability – the scientists found something exciting. They could separate the oil from the water by causing individual droplets of water to coalesce and spread across the surface. As a result, by fusing together more and more, the water droplets separated from the oil.

Next, the researchers found a way to treat a titania surface in order to make it responsive to visible light, as it normally responds to to ultraviolet light which only makes up 5 percent of sunlight. The scientists used a layer-by-layer deposition technique to build up a film of polymer-bound titania particles on a layer of glass and then they dip-coated the material with a simple organic dye.

The new surface turned out to be highly responsive to visible light, producing a change in wettability when exposed to sunlight that is much greater than that of the titania itself. When activated by sunlight, the material proved very effective at “demulsifying” the oil-water mixture — getting the water and oil to separate from each other.

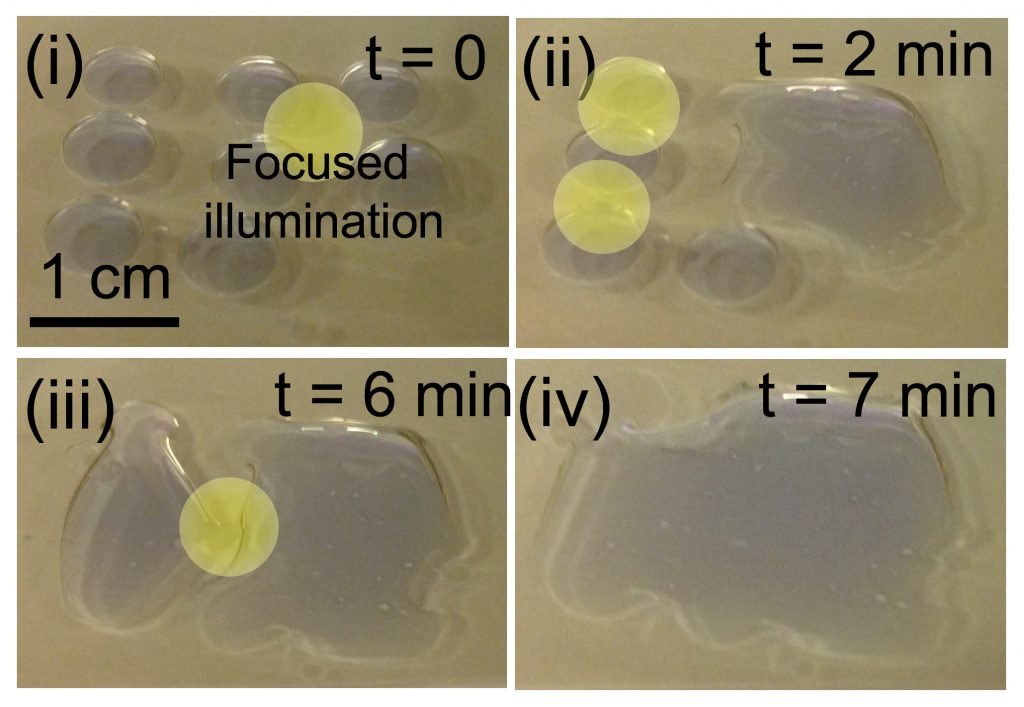

In a series of experiments, the team demonstrated that the same effect could also be be used to drive droplets of water across a surface. Using a moving beam of light to selectively change the material’s degree of wetting, the researchers managed to direct a droplet toward the more wettable area, propelling it in any desired direction with great precision.

The scientists say such systems could be designed to make microfluidic devices without built-in boundaries or structures. The movement of liquid — for example a blood sample in a diagnostic lab-on-a-chip — would be entirely controlled by the pattern of illumination being projected onto it.

The research, reported in the journal Nature Communications, was supported by the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, through the Center for Clean Water and Clean Energy at MIT and KFUPM.